Figure 1: Cover of Perils of Perception

Bobby Duffy, in his 2018 book ‘The Perils of Perception’, put forward a tentative set of proposals for how we could ‘manage our misperceptions’. These are summarised below, together with thoughts as to how we could apply them to geographical education in the context of aiming to achieve a fact-based, optimistic worldview. Firstly it is worthwhile quoting from Duffy’s preamble:

“[W]e’re not just wrong about the world because our media or politics are misleading us. Our ignorance and misperception of facts are long-standing, and they persist in very different conditions over time and across countries” (Duffy, 2018: 231). Although, tellingly, he goes on to say “While we shouldn’t think there was ever an age of perfectly neutral information, we shouldn’t kid ourselves: we’re travelling towards a world where disinformation has more opportunity to be created and travel faster” (p237).

Duffy’s suggestions

Duffy is keen to stress that “there is no magic formula to deal with our misperception” (p248) but also asserts that there are real and practical things that we can do. These begin with points related to how we think as individuals, before moving through to society-based actions

1. Things are not as bad as we think – and most things are getting better. This chimes with the whole gist of Factfulness. In Geography, we could set the ‘Ignorance test’ from Gapminder to our students; or perhaps when setting the context for teaching hazards, we could use graphs which show the deaths from hazards decreasing (we do this at my school). Paul Turner (@geography_paul) has created a scheme of work based on Factfulness, which has its own ‘rules of thumb’ for those who wish to obtain a fact-based worldview (Rosling et al, 2018). Infographics such as Figure 2 could be placed on walls of classrooms or handed out to students at the start of a unit on development – and then discussed. I have also shown all or part of the two hour-long documentaries, as well as some of the thought-provoking YouTube videos and TED talks, which are found on the Gapminder website.

Figure 2: The World as 100 People over the last two centuries

Source: https://ourworldindata.org/

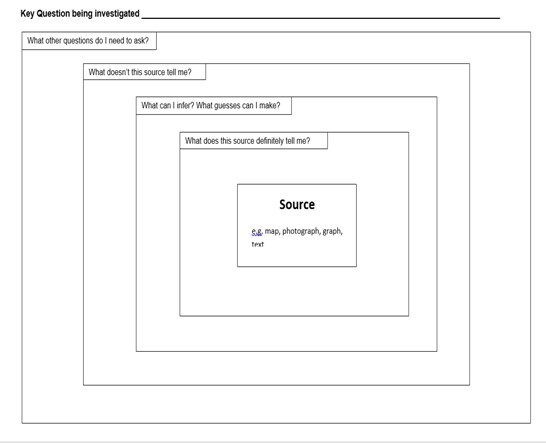

2. Accept the emotion but challenge the thought. As humans we are mentally predisposed to be affected emotionally by certain themes, such as human tragedies, but we should temper our immediate emotional reactions with more deliberative, contemplative thought. This is more difficult – but as educators we could, for example, set more exercises involving the deeper interrogation of images – such as ‘layers of inference’ activities, which, as Margaret Roberts points out, are common in historical education but which have only recently been adopted by a groundswell of geographers (see Figures 3a and 3b). For example, students could be given this image…

Figure 3a Man and truck in Calais, 2014

Source: Philippe Huguen / Getty, via https://www.newsweek.com/migrant-lorry-drops-more-double-britain-483218

…and then asked to question it using the following template:

Figure 3b Layers of inference framework

Source Margaret Roberts / GA via https://slideplayer.com/slide/4055725/

3. Cultivate scepticism, but not cynicism. Most of us will have come across the inveterate cynic in our classroom – and even our staffroom – who claims that “climate change is not real”; “poor countries will stay poor – the people are lazy”. Cynics tend to be oppositional and have a negative mindset. Scepticism, on the other hand, is a useful skill to cultivate – we should constantly question the veracity of the information we receive and encourage our students to do so to. ‘Layers of inference’ photo interpretation activities are one way of achieving this – and why not apply the ‘layers of inference’ grid to other kinds of sources – such as newspaper headlines, cartoons, emails, speeches, etc?

4. Other people are not as like us as we think. This is not to say that we should not empathise with others – rather, this means that we should not assume that ‘all we see is all there is’. In Geography, we should continue to seek out opportunities to see things from others’ points of view. Decision-making and Issues-based exercises could assist us in this task, as could using resources such as ‘Dollar Street’ (https://www.gapminder.org/dollar-street/matrix – see Figure 4) and using real diary extracts and video footage from people living in other parts of the world.

Figure 4 – Dollar Street

Source: https://s3-eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/static.dollarstreet.org

5. Our focus on extreme examples leads us astray. There are many examples where we stereotype people, often assuming the worst – the news does not help us in this regard. As Duffy says, “We’re naturally drawn to extreme examples, which means that true but vanishingly rare events or populations take up more of our mental capacity than they deserve” (p241) When asked about migration, our students (or indeed, our more populist-inclined politicians) may well think about people on boats in the English Channel without putting these flows (in the realm of a few hundred a year) in the context of economic migration (hundreds of thousands a year). Judicious use of proportional symbols, graphs and maps could help us to counter this tendency.

6. Unfilter our world. It is well known that online, we are to a large extent a slave of algorithms: we live in a ‘filter bubble’. We reinforce this by ‘liking’ and ‘sharing’ opinions: this results in an ‘echo chamber’ effect. Governments and corporations have their role to play in dissolving these filters, but so have educators. Using old favourites like ‘devil’s advocate’ debates could be used more often, and pupils could be given a range of media articles to compare, on issues such as migration and population growth.

7. Critical, statistical and news literacy are going to be difficult to shift, but we can do more. The task will not be easy: “we won’t be able to teach the human out of our kids, and critical thinking is not a universal guard against misconceptions” (p 244) – but just because a task is difficult does not mean that it should not be attempted: Duffy refers to addressing news literacy as “becoming the social, cultural and political challenge of our time” (ibid). As educators we need to continue the fight against the trend of transmitting knowledge, and instead increase the proportion of our time dedicated to critical thinking, psychology, and the study of statistics – and these should be delivered by more than one subject. The breadth of subjects our students follow should also be widened:

- We should encourage the growth of AQA’s Extended Project Qualification – rather than restricting it to the most able students, this should be offered more widely; 60% of its marks come from the student engaging with the process of its completion, for example by undertaking a critical literature review

- Schools and colleges should look again at offering Critical Thinking at A Level – and it is a shame that OCR’s Thinking and Reasoning Skills Level 2 Award was withdrawn last year: with media literacy and fact-based education becoming more important, surely the time has come for a respected and well-promoted replacement?

- The International Baccalaureate is another way of encouraging students to develop their critical, statistical and news literacy, via its Theory of Knowledge and Extended Essay components

- The IB’s Middle Years Programme may be another way of developing critical and reflective – as well as global-minded – students

8. Facts still count, and fact-checking is important. It may sound trite, but facts should be used carefully to back up arguments. I say carefully, because, as Duffy points out, the academic literature on the use of facts to correct misperceptions shows very mixed results. In the classroom, in assemblies like this one and this one, and in presentations, I refer to several ‘killer’ facts and graphs, many of the latter gleaned from Max Roser’s thorough, contemporary, and compelling website ‘Our World in Data’ (see Figure 2). The optimist in me still likes to think that these facts will do the trick. But I am also aware that “humans naturally look for confirming information, and discount disconfirming information”. Nevertheless, I am heartened by the existence of cognitive dissonance: with enough evidence, initially unconvinced people will switch, as the ‘pain’ of persuading themselves to accept their original opinion despite the volume of evidence against it outweighs the ‘pain’ of admitting to themselves that they were wrong.

So how can we adapt this insight into our practice as educators? We can instill the importance of fact-checking throughout a child’s education, we can pick up on misconceptions, and we can pick up on students who quote inaccurate information. I remember setting a ‘cover page’ activity to Year 9 students on the topic of Hazards and a handful of them mindlessly typed ‘tsunami’ into a search engine, and the first image was this digitally altered image (Figure 5). This provided a great opportunity to discuss the reliability of sources.

Figure 5 Digitally altered photo of a tsunami

Source: I am unable to attribute this to its original creator, but this was found at

http://jimdrake.blogspot.com/2011/01/technology-tsunami-hits-snyder-texas.html

A fun activity to make students sit up and take notice of inaccuracies is to find a mistake in a textbook and offer a reward to the first student who notices it. This could also be applied to those who notice mistakes in your own worksheets. Peer marking for factual errors can also help to remove any stigma which you fear you might be getting as a ‘nit-picking pedant’!

Moreover, teachers should aim to ‘get in there first’ – by teaching accurate world views in primary schools and in the early years of secondary education, rather than leaving until later in the system, when many students following certain subjects may not get to be aware of this all-important life skill.

9. We also need to tell the story. The use of narratives and anecdotes to persuade others of a point of view is as old as rhetoric itself. They have a power over the human mind that pure facts struggle to muster. When teaching immigration, for example, it is important to focus on real life stories as well as using quantitative data about the scale of net migration or its economic impacts. Examples abound, and I use a Guardian Weekend magazine article to personalise migration and to show its range; other resources include https://www.ourmigrationstory.org.uk/

10. Better and deeper engagement is possible. This is where we move from taking evolutionary steps to revolutionary changes! Duffy mentions that more informed deliberation could help to shift misperceptions and reduce ignorance – and one idea from Bruce Ackerman and James Fishkin (2005) is to hold national ‘deliberation days’ where citizens would be invited to participate in public community discussions. People would gather in groups of 500 or so to hear presentations and ask questions of experts or representatives. Attendance would be incentivised, and the events would take place on national holidays, perhaps prior to an election. Could schools adapt this idea and have ‘deliberation days’ on set topics, rather than leaving debating and philosophising to a self-selecting crowd of confident students? This would be a step beyond ‘mock elections’ and it could give ‘pupil councils’ a boost so that they could integrate national and global issues – such as plastic pollution or media bias – into their deliberations. Senior members of corporations, universities and, yes, schools, have ‘away days’ to deliberate on important issues – so why should we not extend this to pupils? Duffy has trialled these with government and other groups and has seen people change their ways of thinking.

I am conscious that my recent seven-minute assembly on global progress may have given students – and teachers – a momentary pause to think about their worldview, but I know that a fuller programme of engagement will be needed to reach a ‘tipping point’ in attitudes.

One other insight that Duffy makes is to draw our attention to the work of Michael Shermer, the founder of the Skeptics Society. A summary of his steps to convincing others of the errors of their beliefs is:

- Keep emotions out of the exchange

- Discuss, don’t attack (no ad hominem and no ad Hitlerum)

- Listen carefully and try to articulate the other position accurately

- Show respect

- Acknowledge that you understand why someone might hold that opinion

- Try to show how changing facts does not necessarily mean changing worldviews

Source: Shermer (2017)

I am immensely grateful to Professor Duffy for giving me a structure on which I can build my deliberations for ‘Educating for Hope’. I hope to build on these in the future and, as always, I welcome further contributions.

David

Ackerman, B. and Fishkin, J. (2005) Deliberation Day (Yale)

Duffy, B. (2018) The Perils of Perception (Atlantic)

Rosling, H, Rosling, O and Rosling-Ronnlund, A (2018) Factfulness (Sceptre)

Shermer, M. (2017) ‘When Facts Backfire’ https://michaelshermer.com/2017/01/when-facts-backfire-why-worldview-threats-undermine-evidence/ accessed 18 January 2019

5 replies on “Educating for Hope – how can educators overcome the Perils of Perception?”

Really interesting article David – thank you.

LikeLike

Thanks Fran – glad you enjoyed it! Psychology is so interesting – I’m reading a bit more about it nowadays (in-between everything else – phew!).

LikeLike

[…] are contentious, and others draw on the same themes as some of my earlier posts, such as this, but here […]

LikeLike

[…] Pupil councils, tutor periods, debating societies and other more innovative forums could be utilised by practitioners to enable students to air, discuss, and test out their opinions. Going the full hog, whole-year or whole-school ‘deliberation days’ could be trialled, much like those promoted by Bruce Ackerman and James Fishkin (2005) . (I have written more about this here.) […]

LikeLike

[…] Pupil councils, tutor periods, debating societies and other more innovative forums could be utilised by practitioners to enable students to air, discuss, and test out their opinions. Going the full hog, whole-year or whole-school ‘deliberation days’ could be trialled, much like those promoted by Bruce Ackerman and James Fishkin (2005) . (I have written more about this here.) […]

LikeLike