“[H]owever uncertain I may be and may remain as to whether we can hope for anything better for mankind, this uncertainty cannot detract from the maxim I have adopted, or from the necessity of assuming for practical purposes that human progress is possible. This hope for better times to come, without which an earnest desire to do something useful for the common good would never have inspired the human heart, has always influenced the activities of right-thinking people.”

Immanuel Kant

Using indicators adopted by the United Nations and other international governmental organisations, most aspects of human development have improved in recent decades. For instance, the global under-5 mortality rate has fallen significantly between 1990 and 2020, from 93 deaths per 1,000 live births to 37 per 1,000 in 2023 (World Health Organization, 2025); and the global literacy rate has increased from 36% in 1957 to 87% in 2023 (UNESCO, 1957, 2025). However, the majority of people are not aware of the pace or existence of such improvements. In the 2000s and 2010s, Hans Rosling brought this phenomenon to wider public recognition, and in 2022, psychologists Gregory Mitchell and Philip Tetlock termed this phenomenon ‘general-progress neglect’.

I have been interested for several years as to what the reasons are behind this underestimation. My PhD research partly focuses on the role that the secondary Geography curriculum might play in this. Different writers have different ideas; amongst those who have ventured reasons are Mitchell and Tetlock, Max Roser, Bobby Duffy, and, of course, Rosling himself, together with his children Ola and Anna, in Factfulness.

As part of my literature review, I distilled many of the suggestions as to why this may be into a brief list. (I will withhold any of my suggestions as to the role of geography education at this point.) I would love to hear from any academics, teachers, researchers, or members of the public who have their own suggestions to add to the list!

Before I proceed, of course I have simplified the contents and the referencing – this is a blog post, not an academic article! Anyway, here goes:

Perceptual-cognitive processes

- Confirmation bias: We are biased towards findings that confirm what we already believe to be true (see, for example, Kahneman)

- Negativity bias: Negative information receives more processing and contributes more strongly to the final impression than does positive information, so we react more quickly to bad news than to good news (Silka, Pinker)

- Nostalgia: People tend to compare vivid examples of the present with a simplified past (Silka)

- Numeracy: People fail to appreciate temporal differences in contextual features, such as changes in population levels that parallel changes in absolute crime rates (Silka)

- Availability heuristic: We are likely to base our views and decisions on the information which comes to our mind most readily, and information from the media is often negative (Kahneman)

- Outlier effect: In a world in which mostly good things happen, negative outliers tend to be disproportionately salient (producing an availability heuristic-driven overestimation of frequency) and are also much more emotionally disturbing (producing rumination about how to avoid these unwelcome outcomes) (Mitchell & Tetlock)

- Stereotyping: We sometimes have preconceptions of people and places. This leads to stereotyping, despite and changes that take place

- Conformity: We like to go along with the majority and ‘fit in’ with what others in our group believe (Kahneman). This can lead people to adopt views which may not accord with objective realities, and towards “fundamentalisms that proffer transcendental absolutes at the expense of rational thinking” (Lowenthal, 2002, p. 70)

- Error-management: People may arguably see it as more prudent to make the error of overestimating societal problems than the error of underestimating them, and the price of vigilance is worry (e.g., Haselton & Nettle, 2006)

- Moralisation: Complaining about problems is a way of sending a signal to others that you care about them, so critics are seen as more morally engaged (Mitchell & Tetlock)

- Rising baseline syndrome: As we get used to higher standards of living, human rights, and so on, we base our expectations on our current condition, rather than the original baseline. Mark Henry calls this Progress Attention Deficit.

Other factors

“The media world is one of general anxiety punctuated by episodic disaster”

David Lowenthal

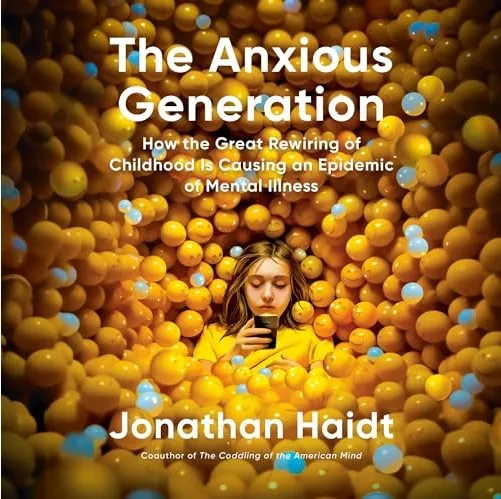

- Media: The media has always tended towards drama. As the adage goes, ‘if it bleeds, it leads’. Jean Baudrillard wrote about the challenges involved in dealing with an ‘information blizzard’ back in the 1990s, but at least then we could hunker down and escape the media. But the impact of the internet and the ubiquity of smartphones has made it hard to escape the blizzard. And, over the past decade or so, big tech companies have pushed us towards short-term, unusual, and often negative content, as this both attracts and retains our attention. These companies exploit some of the psychological dispositions featured in the list above. Read more about how doomscrolling is feeding mean world syndrome here.

- Education: Ola Rosling has claimed that “teachers tend to teach outdated world views”, that “books are outdated in a world that changes”, and that “there is really no practice to keep the teaching material up to date” (Rosling & Rosling, 2014). Rosling et al (2018) later claimed that people’s worldviews were “dated to the time that their teachers had left school” (p. 11), and they asked “Why are we not teaching the basic up-to-date understanding of our changing world in our schools and in corporate education?” (p.247). I wonder whether these claims are valid. They surely can’t apply to all teachers in all schools in all countries? Making progress towards investigating these claims has been one driving factor behind my research.

- Some political and intellectual shifts have arguably made it harder to identify, evaluate, and, yes, celebrate human progress where it has occurred. The impact of postmodernism and the (in many ways positive) influence of ‘critical’ and radical intellectual movements has been claimed as a reason why it is not fashionable in many circles to talk about progress: people who talk about things gradually improving are dismissed as being both naive and embarrassing. This links with the psychological claim of moralisation made above, whereby complaining about problems is a way of sending a signal to others that you care about them, so critics are seen as more morally engaged and therefore more virtuous.

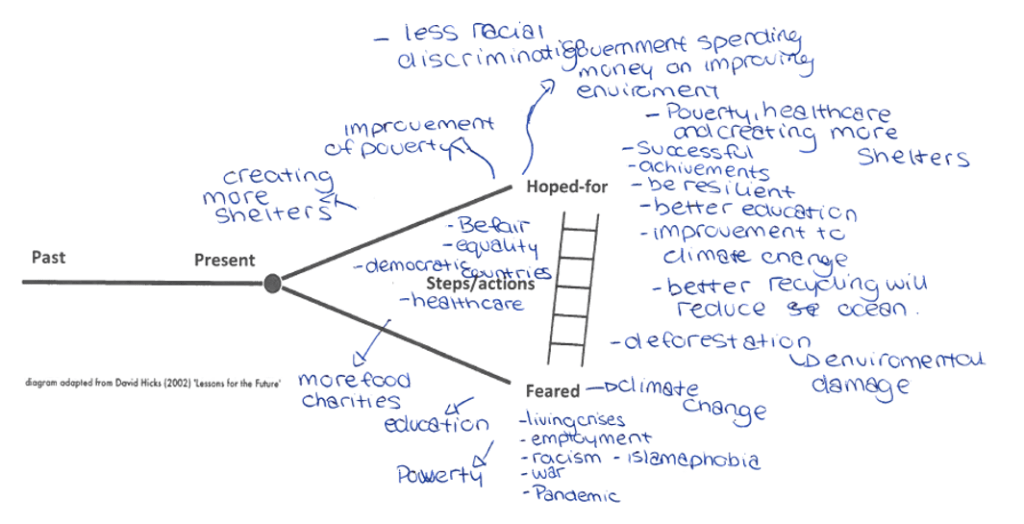

Let me finally emphasise that being more aware of things that are getting better does not mean that we should pay less attention to things that are getting worse. I worry a lot about the things that are not going well in this world. In many ways, being aware of positive trends might give us hope that we will face down the many crises that face humanity. I expand on some of these thoughts here.

Max Roser has a great three-line way of thinking about this – check it out here.

What do you think about the suggestions above? Have I missed any out?